National Road/Zane Grey Museum

8850 East Pike

Norwich, OH 43767

PHONE:740-872-3143

1-800-752-2602 (toll free)

July 10, 2005

This modern museum has three major exhibit areas.

First is the National Road, early America's  busiest land artery to the West. The

National Road was proposed by George Washington. He said "Open a wide door

and make a smooth way".

busiest land artery to the West. The

National Road was proposed by George Washington. He said "Open a wide door

and make a smooth way".

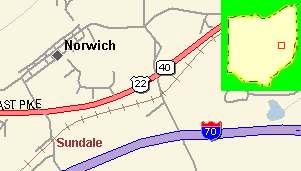

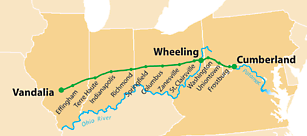

Beginning in Cumberland, Maryland and crossing six states,

the National Road travels over 700 miles, past historic landmarks, forested

mountains, industrial towns and modern cities, rich farmland and pastures, to

reach the Mississippi River and the Eads Bridge at Vandalia, Illinois.

Conceived by Albert Gallatin, Secretary of the Treasury under Thomas Jefferson,

the National Road was the nation's first federally funded interstate highway. It

opened the nation to the west and became a corridor for the movement of goods

and people. It was begun in 1806 and was nicknamed the "Main Street of

America". During this time Thomas Jefferson was President and Ohio had been

admitted to statehood just three years earlier. On March 22, the Ninth Congress passed an act creating the first Federally supported

road in the U.S.

The Act of Congress authorizing the National Road required distinguishable marks

or monuments to appear at regular intervals along the Road. In accordance with

this stipulation, milestones were set at one-mile intervals along the north side

of the Road. However, since the act included no specifications, the design and

construction material of the milestones varied. In Ohio, the markers were square

with curved heads. The five-foot tall markers were set directly into the ground

with about three feet exposed. Each stone indicated the distance to Cumberland,

Maryland, (where the Road began), at the top center, and the name of and mileage

to the nearest city or village for east and westbound travelers. The earliest

milestones were fabricated of a reinforced cementitious material in the 1830s.

These concrete markers weathered poorly and many were replaced with sandstone

markers in the 1850s. Later, concrete was used to replace some of the sandstone

markers. Eighty-three existing milestones have been documented with the greatest

number in the eastern counties. By the 1920s a uniform highway numbering system,

with standardized road signs, identified the National Road and U.S. 40.

S-bridges are a unique feature of the National Road. Folklore abounds as to why

they were built. One story suggests the s-shape forced drivers to slow their

horses, reducing the chance of accidents. Some said the bridges were originally

built around huge trees, while others claimed they were the result of inebriated

bridge builders. However, there is a logical explanation for Ohio's crooked

bridges. The National Road seldom encountered streams and rivers at a direct

90-degree angle. In order for bridges to be constructed so as to cross these

bodies of water at 90 degrees while maintaining the direction and location of

the Road, an S-shaped design was selected as the solution. The S-shape easily

accommodated slow-moving droves of animals and horse and oxen-drawn wagons, but

with the advent of higher-speed automobile traffic they became a hazard. Most

were soon bypassed, although at least one - near Hendrysburg - was straightened

in 1933 and continued in use for

S-bridges are a unique feature of the National Road. Folklore abounds as to why

they were built. One story suggests the s-shape forced drivers to slow their

horses, reducing the chance of accidents. Some said the bridges were originally

built around huge trees, while others claimed they were the result of inebriated

bridge builders. However, there is a logical explanation for Ohio's crooked

bridges. The National Road seldom encountered streams and rivers at a direct

90-degree angle. In order for bridges to be constructed so as to cross these

bodies of water at 90 degrees while maintaining the direction and location of

the Road, an S-shaped design was selected as the solution. The S-shape easily

accommodated slow-moving droves of animals and horse and oxen-drawn wagons, but

with the advent of higher-speed automobile traffic they became a hazard. Most

were soon bypassed, although at least one - near Hendrysburg - was straightened

in 1933 and continued in use for several more years. There is still an

S-shaped

bridge in Zanesville, Ohio, not far from the Museum in Norwich.

several more years. There is still an

S-shaped

bridge in Zanesville, Ohio, not far from the Museum in Norwich.

By the late 1830's it was evident that additional money would be needed if the National Road were to remain in good repair. Failing to find another way, the ownership of and responsibility for the National Road were handed to the various states. Almost immediately, they began to construct tollhouses. Tolls were charged travelers much as on modern toll roads today.

An example of tolls collected were: For every chair, coach, phaeton, chaise, stage wagon, coachee or light

wagon with two horses and four wheels $12. For either of the carriages last mentioned with four horses $12. (The list goes on extensively)

Usually travelers found use of the road so convenient and the rates so reasonable that they paid the tolls willingly.

The Searight Tollhouse is one of several still in existence. The unique shape immediately

identifies the structure and the many windows permit the gatekeeper a distant view in all directions.

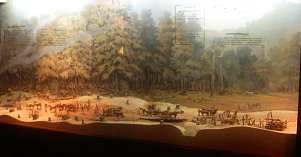

The National Road soon became a congested passageway not only for people and vehicles but for moving herds of animals. Much of the increased traffic was

composed of pigs, geese, sheep, cows, and other livestock being herded by drovers toward the nearest town or marketplace.

It often took several weeks for the slow moving animals to reach market. The drovers and their animals might be headed for Wheeling, or even Baltimore, where there were good markets.

Overnight stops for drovers required special drover's stations, with pens of various sizes to provide safekeeping for the livestock, plus an inn of sorts where the drover could get a meal and drink. Most drover's stations did not offer sleeping accommodations.

Drover's stations did not cater to stage line coaches but they were often used, and

liked, by the wagoneers. To accommodate the increasing number who wanted to travel along the road, stage lines soon competed for passengers. Their colorful names and coaches soon developed individual reputation, as did their drivers. Speed was more important than comfort. The stage lines hired or franchised a coach stop about every twelve miles where the coaches could pull in for a team of fresh horses and an occasional passenger. The exchange of horses was accomplished so quickly passengers seldom could even get out to stretch their legs.

As schedules increased, a stage stop manager would perhaps add an office to the side of his house as a place to keep records, collect fares, and otherwise conduct business. The busy stops maintained good horse barns and often had a blacksmith and a repair shop.

A 136 foot diorama of

the National Road plus many objects illustrate this theme. In 1925 the name of

the road was changed to Route 40.

seldom could even get out to stretch their legs.

As schedules increased, a stage stop manager would perhaps add an office to the side of his house as a place to keep records, collect fares, and otherwise conduct business. The busy stops maintained good horse barns and often had a blacksmith and a repair shop.

A 136 foot diorama of

the National Road plus many objects illustrate this theme. In 1925 the name of

the road was changed to Route 40.

The second exhibit is about Zane Grey, the "Father of the Adult Western." The Zanesville

author wrote more than 80 books. Pearl Zane Gray/Zane Grey was born January 31, 1872, at Zanesville, Ohio, where he acquired his interest in outdoor life and story telling. After a short career in baseball and several years of half-hearted practice in dentistry, a trip to the West fired his imagination and he wrote

more than fifty Western romances that rank him as one of the most popular writers in the world.

As a boy in Zanesville, Ohio, Zane Grey acquired a passion for hunting. When royalties made him rich,

Grey pursued big game and gathered material for his books in remote Western areas. But in 1929 he realized that killing game destroyed the wilderness he loved. He then

quit hunting and preached conservation. Zane Grey employed guides and hunters to organize wagon trains for expeditions into the Western wilderness for hunting and for taking notes on scenery and about characters that he used in his books.

He favored New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona for stalking big game. His study is recreated, plus many manuscripts

and other memorabilia are displayed.

more than fifty Western romances that rank him as one of the most popular writers in the world.

As a boy in Zanesville, Ohio, Zane Grey acquired a passion for hunting. When royalties made him rich,

Grey pursued big game and gathered material for his books in remote Western areas. But in 1929 he realized that killing game destroyed the wilderness he loved. He then

quit hunting and preached conservation. Zane Grey employed guides and hunters to organize wagon trains for expeditions into the Western wilderness for hunting and for taking notes on scenery and about characters that he used in his books.

He favored New Mexico, Utah, and Arizona for stalking big game. His study is recreated, plus many manuscripts

and other memorabilia are displayed.

Finally, a central portion of the museum is devoted to Ohio art pottery.

Good Luck! Have Fun! and Stay Safe!

Laura